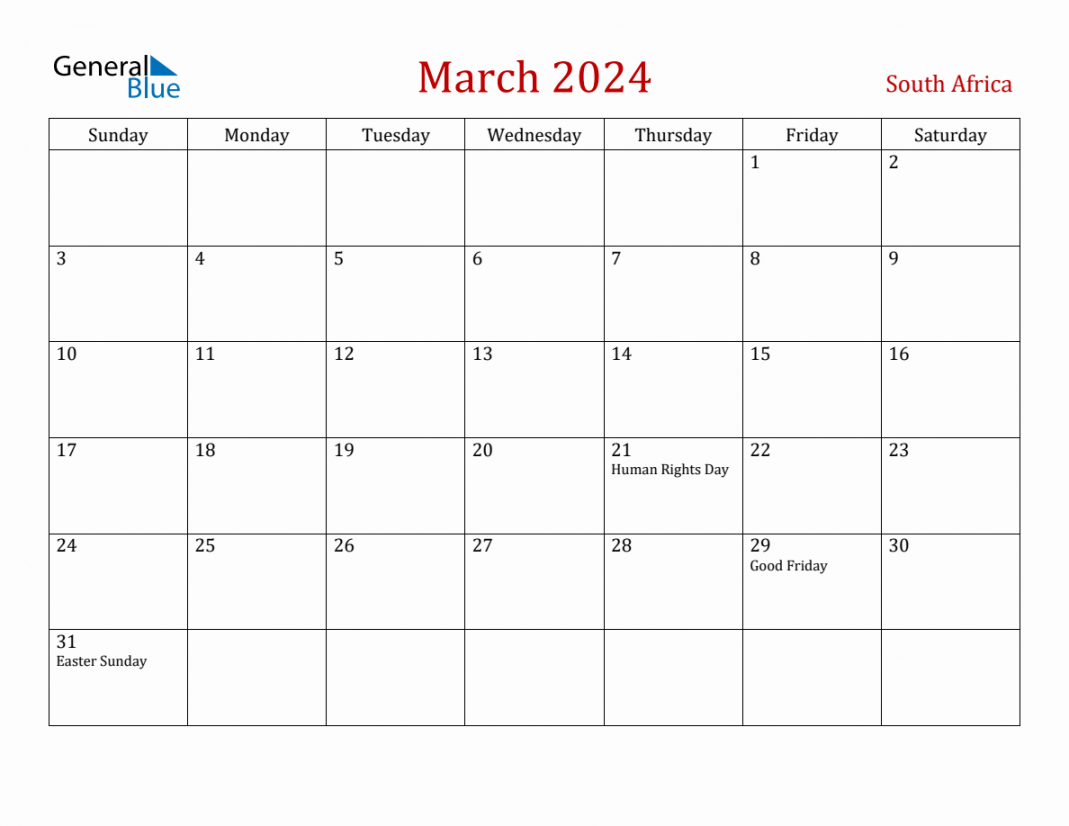

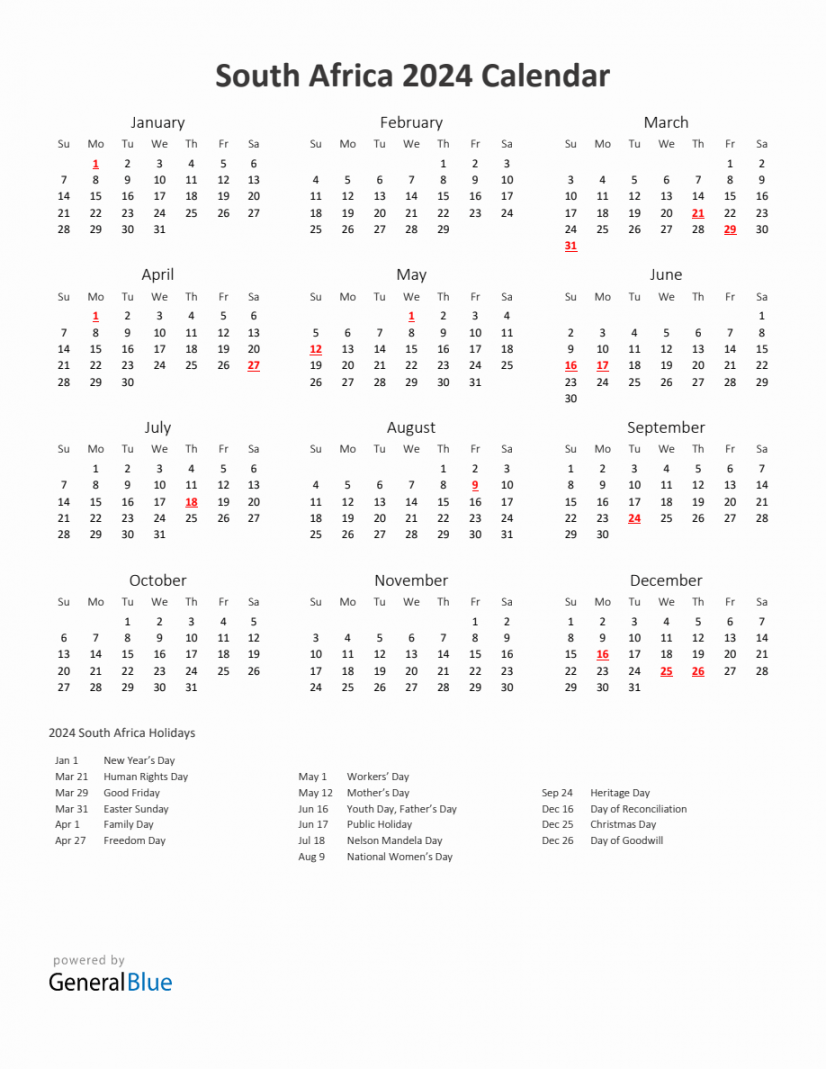

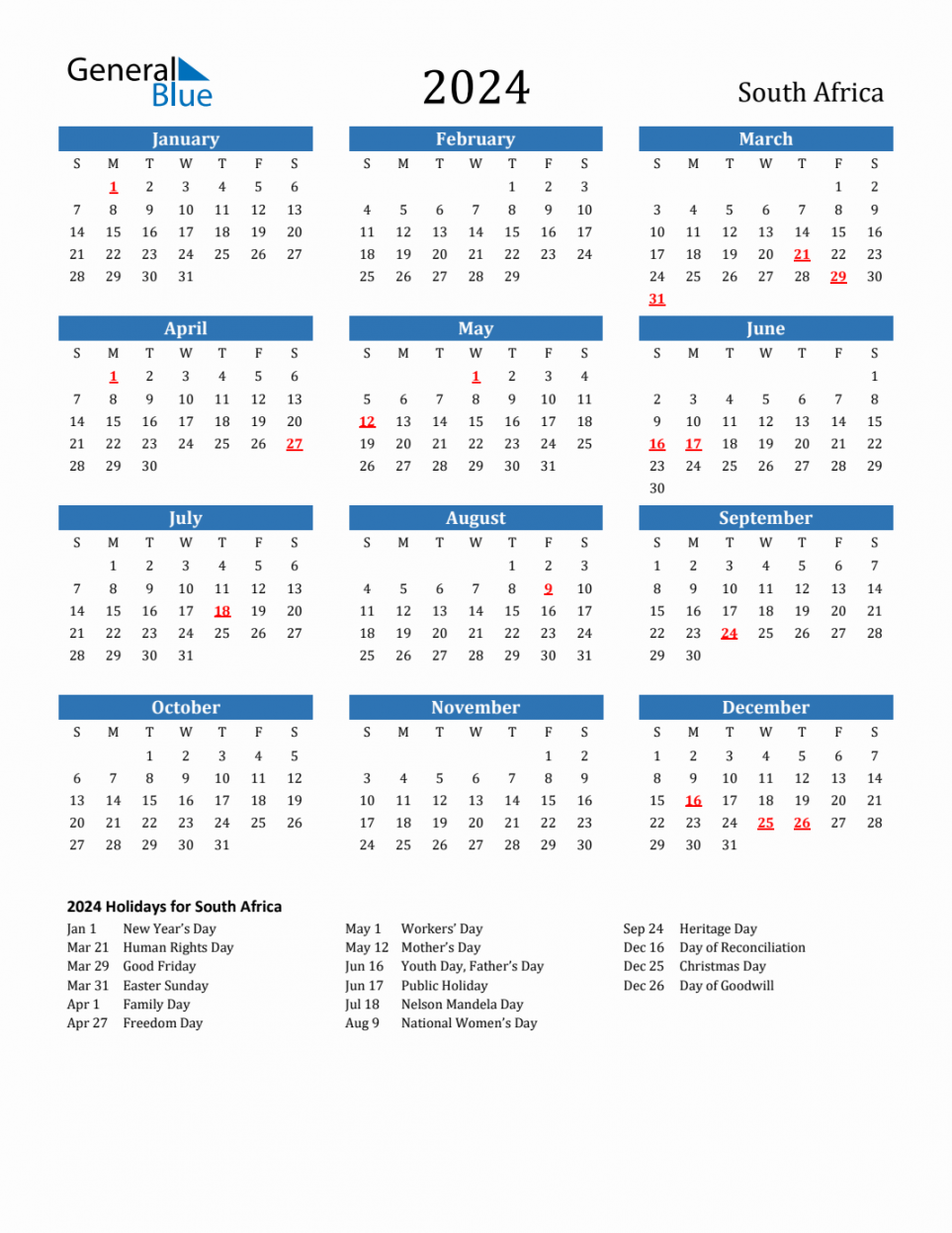

Calendar 2024 With Holidays South Africa

South Africa: Can Ramaphosa secure a 2024 victory?

For the last 12 years, Dimakatso Ragedi has lived with her mother and daughter in a low-cost house in Cosmo City, a residential project in an upmarket suburb of Johannesburg that was co-financed by the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party.

The young woman and her family know too well that power outages are a part of everyday life in South Africa.

Load shedding — the practice of scheduling power cuts to keep the country’s power grid from collapsing — means that Ragedi’s house is often plunged into darkness, her kettle stops boiling, her washing machine grinds to a halt and she has no way to charge her cell phone.

“If the electricity stays away, we use a gas stove and rechargeable light bulbs,” Ragedi told DW.

Dimakatso and her family previously lived in a corrugated iron hut in the Alexandra townshipImage: Siphiwe Sibeko/REUTERS Broken promises

Ragedi’s standard of living has improved since 1994, the year Nelson Mandela became the president of a new post-apartheid democracy. In its first-ever election manifesto, the ANC had promised South Africans adequate housing, water, and electricity. Nearly three decades after taking power, the governing party barely manages to keep the lights on in people’s homes.

Raika Wiethe, who lives in Parkview, a green residential district in the north of South Africa’s economic capital Johannesburg, said that during the first half of the year, she experienced up to 12 hours of power outages every day.

When South African President Cyril Ramaphosa hosted the BRICS summit in August, the energy supply was consistent — but power outages are more frequent now, said Wiethe.

Liberation! Nelson Mandela and Eduardo Mondlane

To play this audio please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 audio

The leaders of the five-country grouping met in Johannesburg to discuss expansion and increasing global influence.

“Cyril Ramaphosa used the BRICS summit to enhance his own standing and significantly increase South Africa’s diplomatic weight in a changing global community,” said political analyst Daniel Silke.

But that matters little to local politics, Silke said.

South Africans are concerned about fundamental problems on the ground, such as poor governance, rising prices, and unemployment, he said.

“The ANC needs to take more responsibility and make sure the lights don’t go out,” Silke told DW.

Eskom, the state-owned utility that produces 90% of South Africa’s electricity, has debts of around €21 billion ($19.8 billion) and is struggling with ailing coal-fired power plants that regularly break down. The company was mired in corruption scandals under former President Jacob Zuma.

Can Ramaphosa secure a second term?

The daily blackouts across South Africa are affecting businesses and households that already suffer from severe inflation amid the country’s weakened economy.

“The biggest fear is that there will be a complete collapse of the power grid,” Ragedi said.

Confidence in the ANC has dwindled. Before every election, the government promises more jobs and more houses for the poor, as well as less crime and corruption, Ragedi said. “But we are moving toward conditions like in Zimbabwe.”

Neighboring Zimbabwe went from a well-diversified economy into the region’s problem child during nearly four decades under the rule of former President Robert Mugabe.

“We are a democracy, however at the moment it looks like we are an autocratic country, it is in shambles,” Ragedi said of South Africa.

When Ramaphosa first became president in 2018, he was seen as a beacon of hope after former president Jacob Zuma resigned amid corruption allegations .

But in 2019, Ramaphosa’s party only managed to garner 57% of the vote — the lowest share ever for the ANC.

Will Ethiopia’s bid to join BRICS push Western allies away?

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

ANC losing ground

For Priyal Singh, a fellow at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), it is the first election in South Africa’s post-apartheid history that will be highly contested.

“For the first time, we are predicting that support for the ANC will fall below the 50% threshold and plunge us into a turbulent period of coalition politics,” he told DW.

Political resistance has been brewing for a long time.

In August, seven opposition parties agreed to form a coalition to replace the ruling ANC — if the party fails to win an absolute majority in 2024. Among them is the country’s largest opposition party, the Democratic Alliance.

At the local government level, the ANC has had to form political partnerships as far back as 2016. “These coalition governments have not been able to address the administrative deficiencies that have plagued many major cities,” said Singh.

A stagnant economy

Despite all the scandals that have surrounded Ramaphosa’s government, he still benefits from a substantial support base in the ANC, according to Singh. He has survived politically — notwithstanding the attacks by the pro-Zuma factions within the party. That speaks to how smart Ramaphosa is as a politician, he said.

In post-apartheid South Africa, there has been no democratically elected president who has lasted a full two-year term, Singh said, adding that “I trust him to do it despite the political divisions.”

The most pressing problem for Ramaphosa, he said, is the economy, which has been stagnant for more than a decade and has grown by barely 1% so far. This tiny increment is totally insufficient to address major challenges such as unemployment, inequality and poverty, Singh said.

The interruption of the power supply has held the economy hostage for years. The priority, he said, was to fight corruption, including in the ANC.

Trust in South Africa’s government declines

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Ramaphosa said that abuse of power by his predecessor Zuma led to the hollowing out of many state-owned enterprises, key agencies and institutions.

“Ramaphosa has tried to address these tasks in recent years, but he simply has not gone far enough,” Singh told DW.

According to Singh, voters expect the president to stop being governed by a committee — the ANC’s National Executive Committee — and make some tough decisions on his own to revive the South African economy.

“Most South Africans are wondering if we can maintain our very fragile democratic order, or if we will fall, and South Africa will implode,” he said, adding that the country would like to see a turnaround in order to secure a future for the next generation.

Ragedi also wants to see a new political power installed — and a more stable life for her young daughter.

“We hope for change,” she said.

This article was originally published in German.

While you’re here: Every weekday, we host AfricaLink, a podcast packed with news, politics, culture and more. You can listen and follow AfricaLink wherever you get your podcasts.